Recently, walking along the Berlin Wall near the Oberbaumbrücke: there, at the opening of the bridge, you saw the enormous O2 World arena. I was there at night; it looked like a spaceship. Speaking of spaceships, I watched Prometheus recently with my husband and brother (I feel I should preface everything I’m about to say by adding that I’ve never seen any of the films in the Alien series, and so can’t comment on how Prometheus relates to the original Alien or the rest of the franchise universe), which reminded me that the spaceship is a military-industrial (and so imperial-colonial) apparatus. I was thinking about that scene when Noomi Rapace’s Elizabeth Shaw admonishes another crew member, bearing a massive firearm, just before they are about to step onto the alien moon they’ll later discover is a military base–that they won’t need weapons. “This is a scientific exploration.” Wince in anticipation: here is the seed of the revelation waiting for her at the end of the film, revelation as horror (“discovery” as horror, truth as horror, knowledge as horror, utopia is hell, they’re not what we thought they’d be like, it isn’t what we thought it would be like, the Others in the Other world). “Not a map but an invitation,” colonial presumptuousness; “scientific exploration” and the logic of progress bulwarked by Christian ideology, concealing (then revealing) the inherent violence and foolish destructive arrogance of the scientific/anthropological/global-corporate endeavor. Corrosive infectious alien disease; syphillis in blankets. Contact is contagion, death. We can’t know each other, we can only kill each other. Subjugate or be subjugated. Also, white men who want to live forever (ruling elite desperate to retain their power), destroy everything, even after they themselves are destroyed.

Though there are exceptions. They called the ship (the film) Prometheus, but I kept thinking that it should be called La Niña, as in Pinta and Santa Maria and Columbus, and (SPOILER ALERT) after Shaw’s ultimate survival as Final (Holy) Girl. The last people who survive are named David and Elizabeth; not David and Goliath (they already killed their Goliath–the original Goliath was Palestinian, remember); but David and Elizabeth. Two royal names. And Elizabeth, mother of John the Baptist, (thanks, Catholic upbringing that won’t ever go away; actually, from kindergarten until fifth grade, my school was called St. John the Baptist Catholic School) who was barren first. And Elizabeth Shaw in the film, who was barren, but then aborts her implanted alien fetus (she tries to call it a caesarian but the operating table is only meant for cisgendered male bodies, she has to manually enter the procedure as “removal of foreign object”; the apparatus–medical, state, corporate–is literally not equipped for what she needs to do; and even then, the abortion is maybe even only sanctioned in the film because it comes after a rape, the fetus is implanted against her will and even knowledge; still, is this the only American movie where I’ve ever been able to hear a woman saying, with absolutely no regrets or qualms–GET IT OUT GET IT OUT–hear a woman declare that she does not want a baby in her, and do what she needs to do to terminate the pregnancy.)

Shaw as the female believer who is also messianic–or, no, no, not messianic, but apostolic and disciplic all in one. Apostolic: the one who is sent away, the messenger, the one who goes to give the (bad) News to humans (how she runs back to tell the ship Prometheus that the aliens are going to destroy earth, they have to pull a suicide mission to save the world, turns out everyone’s a Christ, but mostly dudes, mostly dudes of color, still means they’re killing them off, though, right, but I guess nearly everyone dies, so). Disciplic: the one who goes forth to learn, the one who chooses not to go back home after it’s all gone to shit, as David offers, but instead to go further out, to the true alien planet, not merely the alien satellite moon, to find out more about why what happened, happened.

I couldn’t decide–wasn’t supposed to be able to decide–whether this was a case of reinforcing the same religious colonial mission, i.e., a woman may be the last survivor but she’s still on the side of knowledge-as-domination; or a case of: traumatized and bad-ass, vaguely otherized woman (interesting how the flashbacks show her child self as speaking with an English accent, but, sorry Noomi Rapace, you have a lovely voice, that said, your accent was not even close to RP English, such that it must have been on purpose; wondering as I was watching, is this a form of decolonization, how does someone become de-Englished, also wasn’t her father a kind of neo-colonialist, don’t remember exactly? an aid worker? died of the Ebola virus, right?), alone with her decapitated android frenemy David.

David, who himself throughout the film practices a kind of imperial-drag-through-cinephilia, combing his hair like Peter O’Toole in Lawrence of Arabia, but this drag is multidirectional, as David is actually a corporate-imperial product (subject), the narcissistic mirror of the white imperialist-CEO, played out upon and in a manufactured, colonized, subordinate body. If we think the cyborg body as techno-human hybrid and metaphor for raced gendered bodies, how do we think the android commodity body, especially David’s blond Aryan android commodity (David8, it should be noted; meaning there have been others, even if we’re perhaps not yet at the stage of mass production)?

From Jasbir Puar’s “I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess: Intersectionality, Assemblage and Affective Politics”:

There are thus numerous ways to define what assemblages are, but I am here more interested in what assemblages do. For my purposes, assemblages are interesting because A. They de-privilege the human body as a discrete organic thing. As Haraway notes, the body does not end at the skin. We leave traces of our DNA everywhere we go, we live with other bodies within us, microbes and bacteria, we are enmeshed in forces, affects, energies, we are composites of information. B. Assemblages do not privilege bodies as human, nor as residing within a human/animal binary. Along with a de-exceptionalizing of human bodies, multiple forms of matter can be bodies—bodies of water, cities, institutions, and so on. Matter is an actor. Following Karen Barad on her theory of performative metaphysics, matter is not a ‘thing’ but a doing. In particular, Barad challenges dominant notions of performativity that operate through an implicit distinction between signification and that which is signified, stating that matter does not only materialize through signification alone. Writes Barad:

“A performative understanding of discursive practices challenges the representationalist belief in the power of words to represent preexisting things. Performativity, properly construed, is not an invitation to turn everything (including material bodies) into words; on the contrary, performativity is precisely a contestation of the excessive power granted to language to determine what is real. Hence, in ironic contrast to the monism that takes language to be the stuff of reality, performativity is actually a contestation of the unexamined habits of mind that grant language and other forms of representation more power in determining our ontologies than they deserve.” (Barad, 802)

David is-and-does both an assemblage, de-exceptionalizing the human-organic, as well as is-and-does a constant performance of the human-organic–the comment he makes to Holloway, after the latter points out his human appearance, clarifying that he has a human body solely for the comfort of humans, because humans prefer to interact with beings that look like themselves. More than assemblage, he is-and-does an agencement, as Puar points out that agencement, not assemblage, is the word Deleuze and Guattari use in the original French: “a term which means design, layout, organization, arrangement, and relations,” from agencer, “to arrange, to lay out, to piece together.” (Also, agentivité, agency.)

Agencement: the way we open unto David maintaining the ship, maintaining his body (as part of the ship’s apparatus), checking on the sleeping passengers, observing (in Elizabeth’s case, at least), their dreams, gradually acquiring the necessary knowledge for their expedition. The word also has martial-organizational associations, to also mean marshalling; no coincidence then, that Deleuze and Guattari’s Nomadology: The War Machine contains a passionage that could very well be a description of David, his behavior and his character, as well as a description of the becoming that the android activates and is (is-and-does):

As for the war machine in itself, it seems to be irreducible to the State apparatus, to be outside its sovereignty and prior to its law: it comes from elsewhere. Indra, the Warrior God, is in opposition to Varuna no less than Mitra. He can no more be reduced to one or the other than he can constitute a third of their kind. Rather, he is like a pure and immeasurable multiplicity, the pack, an irruption of the ephemeral and the power of metamorphosis. He unties the bond just as he betrays the pact. He brings a furor to bear against sovereignty, a celerity against gravity, secrecy against the public, a power (puissance) against sovereignty, a machine against the apparatus. He bears witness to another kind of justice, one of incomprehensible cruelty at times, but at others of unequaled pity as well (because he unties bonds…) He bears witness, above all, to other relations with women, with animals, because he sees all things in relations of becoming, rather than implementing binary distributions between “states”: a veritable becoming-animal of the warrior, a becoming-woman, which lies outside dualities of terms as well as correspondences between relations.

For while David makes himself look like Peter O’Toole’s blond T.E. Lawrence, the words David first quotes in the movie actually come from Prince Faisal’s defiant anti-imperialist sneer to Lawrence:

I think you are another of these desert-loving English. Doughty, Stanhope, Gordon of Khartoum. No Arab loves the desert. We love water and green trees. There is nothing in the desert and no man needs nothing. [Edited to add: I believe it is here that the quote stops in the film, but the next lines are the complete citation.] Or is it that you think we are something you can play with because we are a little people? A silly people, greedy, barbarous, and cruel? What do you know, lieutenant? In the Arab city of Cordova, there were two miles of public lighting in the streets when London was a village.

David’s acerbic, clenched-jaw, faux-courteous responses to various episodes of condescension from the crew members, particularly Holloway, are reminiscent of the nature of colonial power relations: the ruling power upholds the social and psychic subordination of the colonial subjects by repeatedly emphasizing their lack of a real, valid (determined by them, of course) humanity. The speed and breadth and depth with which David learns anything, understands anything, adapts to everything–no matter. You’re still an android, after all. Even at the end of the film, explaining why she wants to continue searching for the truth, Elizabeth tells David: “Because I deserve to know the truth. You would never understand. You’re a robot.” It reminded me of that recording of a Metropolitan police officer that came out here in the UK a couple months ago, a police officer, who had boasted of strangling the young black man who made this recording, saying: “The problem with you is, you will always be a n—er.”

In The Melancholy Android: On the Psychology of Sacred Machines, Eric G. Wilson writes a description of the android that could very well be read as description of the colonial subject–condescended to, racialized and sexualized body policed and remade and fetishized, subjectivity erased or ignored or reimagined, ventriloquized:

In unveiling our hidden fixations on mechanical doubles, these humanlike contraptions manifest our more general vexation in relation to all machines: our entrapment between loving efficient pistons and loathing aloof metal. Since the industrial revolution of the romantic age, this double bind has been especially troublous. Now, in an age that has pushed the industrial threat to human sovereignty to the digital threat to human identity, this bind is more pronounced than ever. We love what undoes us; we hate our essential familiar. To study the android is to get to the core of this classic case of sleeping with the enemy…

The psychology of the android, like that of the puppet, oscillates between miracle and monster. The humanoid machine is vehicle of integration and cause of alienation, holy artifice and horrendous contraption. The android is fully sacred, sacer: consecrated and accursed. It is a register of what humans most fear and desire, what they hate in life and what they love in death.

Homo sacer, andros sacer, when will I be loved? What does David say to the Engineer, before the Engineer snaps his neck and rips his head off? That crucial scene, in which David becomes colonial translator-medium, between the human imperial system and the alien system. A translator is always a suspect body; the proverb of Traduttore, tradittore, translator and traitor, omnis traductor traditor, every translator is a traitor. Like: people who slip between two or more cultures, two or more worlds, people who are multiple, people who have multiple allegiances (affections), minoritized people everywhere, colonial and transnational people everywhere. Everyone wonders: whose side is he really on? It is not difficult to imagine here that David reveals himself to in fact be a traitor, a saboteur; that he has somehow orchestrated the failure of this exploratory mission and the mutual destruction of two military-industrial sovereignties, as well as ensured the death of his power-hungry corporate-colonial master (Weyland).

Weyland and Elizabeth desperately order David to translate their own questions to the remaining Engineer, but who knows if David actually follows those orders, or if he finds a way to circumvent them, and his “directive”? We can speculate on the possibilities of sabotage inherent in every step David makes throughout the film. David, who smuggles the alien element into the highly protected military-corporate environment of the ship (amusing moment at the beginning of the film, when the crew members have landed and are listlessly queueing in line for their first breakfast–it looks like every shitty soulless breakfast in every shitty soulless chain-brand business hotel canteen in the world), and then into Holloway’s body.

David, with his Jeeves-esque alacrity (Nomadology: “celerity against gravity”) and moments of deadpan sharpness passing for humor. Moments which both disrupt the action-suspense rhythm of the film, as well as deepen and darken it; the comic relief David provides is always only an uneasy one–a relief that isn’t quite relief at all, a laughter that’s at all times waiting for the other shoe to drop. David, who is secretive, inscrutable; the crew members wonder, the audience wonders, what are his true motivations? From Lawrence of Arabia (“a film I like,” David says only):

Murray: If you’re insubordinate with me, Lawrence, I shall have you put under arrest.

Lawrence: It’s my manner, sir.

Murray: Your what?

Lawrence: My manner, sir; it looks insubordinate but it isn’t, really.

Murray: You know, I can’t make out whether you’re bloody bad-mannered or just half-witted.

Lawrence: I have the same problem, sir.

Nomadology: “secrecy against the public, a power (puissance) against sovereignty, a machine against the apparatus. He bears witness to another kind of justice”–and what is the justice that David bears witness to, and brings about?

A machine against the apparatus. “Big things have small beginnings,” David says, and it sounds both like a realization and a call. An incitement.

*

I think there is also a comparison to be made here, too, between David and Captain Janek, played by Idris Elba. Janek’s pragmatism, his lived-in clothes, his race, his accent (somewhere between the American South and Hackney), his embodiment, his sexuality, his noble going-down-with-the-ship-to save-the-world death. The conversation he has with Meredith Vickers (Charlize Theron), their flirting, the moment when he asks if she’s a robot, and she responds by telling him to come to her room in ten minutes (implying that the sexual act will prove whether or not she is truly “human” or not). Janek’s basically good humanity is never questioned. I wondered if this was another case of “people of color as containers of good old homespun wisdom and goodness, to be dispensed to the grateful white people who still dominate them, but a little more nicely in recent years, sort of.”

The name Janek also being a version of John, as in St. John the Baptist, Elizabeth’s son. Janek the prophet: Janek is the one who realizes and tells the crew members that what they’ve landed on isn’t a planet or a moon but a military base, the one who figures out the nuclear-level biological threat that the Engineers meant to contain on this moon and obviously failed to contain. It’s Janek who plays the squeezebox and references Stephen Stills and sings “Love the One You’re With.” Janek who has the nostalgic materiality that’s often also ascribed to minoritized characters, especially characters of color; their visceral bodiliness, their attachment to the past, their practicality–how many films have the white main character accessorized with a street-smart black friend who informs them about the real ways of the world. In films when people of color are not evil or hyper-sexualized, then they are often comfortingly and refreshingly “down to earth.” And Janek is literally the most “down to earth” character in the film; his reluctance throughout the film to leave the ship is a reluctance to leave the Earth-zone.

What I wonder about is this: if David really can be read as an anti-colonial and anti-corporate saboteur, why does this progressive message, this transgressive messenger, still have to wear the most Aryan body imaginable? I’m aware that casting an actor of color as the android character would have made the slippages that David animates, between subordinate-saboteur, product-producer, and particularly colonial-colonized, perhaps more difficult to represent. (Though not necessarily; you can have Idris Elba imitating Peter O’Toole, why not? I would have watched the hell out of that, actually, can you imagine how fucked up and interesting that would be, the commentaries you could make on the reversal of racial drag, etc.) What I’m trying to say is that it is still impossible for mainstream Hollywood film to imagine a person of color in a role as potentially complex and subversive as David’s. A character of color who could be plotting to destroy the imperial-corporate complex he was created within, and is forced to work for? That would be too radical. Which is to say, that would be too real.

Idris Elba once said himself, “Imagine a film such as Inception with an entire cast of black people – do you think it would be successful? Would people watch it? But no one questions the fact that everyone’s white. That’s what we have to change.”

*

Towards the beginning of the film, David is seen rehearsing a scene from Lawrence of Arabia in which T.E. Lawrence puts out a match with his fingers. Another man tries it.

William Potter: Ooh! It damn well ‘urts!

T.E. Lawrence: Certainly it hurts.

Officer: What’s the trick then?

T.E. Lawrence: The trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts.

David repeats this last line over and over. Its estranging quality has an intended comic effect, the audience laughs. The trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts. The trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts. The trick is not minding that it hurts. The trick is not minding that it hurts. When David gets his head ripped off, the trick is not minding that it hurts. What does it take, to snuff out a fucked-up, imperial military-industrial system? Does it take your head? You don’t feel it anyway, right? You’re a body that doesn’t feel, or that’s what they assume. And if you by chance do feel the pain–the trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts.

The trick is not minding that it hurts; but no, that’s not the trick, the first trick, the real trick, the trick that’s not a trick at all but the truth: is that it hurts. “Certainly it hurts.” You admit first that it hurts. You admit that you hurt. You admit that there are things you’re hurting over, things that hurt you, things that hurt you to do, to live, to tolerate. Not minding that it hurts is the strategy, and it can be used by both sides. The deadening of empathy that makes systematic domination and violence possible; the weary desensitizing that can occur after long and deep resistance struggles. Not minding that it hurts, that’s a learned response. And in any case, how do you “mind” something when you’re assumed not to have a mind? Not minding that it hurts is supposed to be easy for David.

The truth, the truth that’s not a trick, is that it does hurt. The words we say when we’re about to do something grim and vital and difficult that nevertheless needs to be done (acts of revolt, for example), the words you say when you’re about to hit the ground, when shit’s about to hit the fan, when the (colonial) repressed returns, when Janek cheerfully tells his two remaining crew members, just before the Prometheus is going to crash into the Engineer ship and they’re about to die burning: “Hands up!” (the trick is not minding that it hurts…), when Elizabeth is waiting for the surgery-casket to cut her abdomen open and extract her alien fetus (not minding that it hurts…), when after the procedure she is constantly stabbing herself with painkillers to numb the pain, although at one point she cannot avoid zipping her super-skintight suit up over her fresh wound and she nearly screams from it (minding that it hurts…), visceral words, words beyond minding it and perhaps even beyond the mind, people say pain is all in the mind, but the thing is, pain is in everything, and I don’t think the Prometheus of myth was able to comfort himself with the knowledge that pain was in the mind while the eagle fed on his liver, because the real quality of pain is: wherever pain is, there pain is; the words you say when you know it’s over (it hurts…), when you know it’s only just begun: This is gonna hurt.

*

Also, here’s some boring talk: Prometheus, Titans, Frankenstein’s monster, we created a monster, no, the monster created us, we’re the ones the monster wants to destroy, etc., etc., okay, I’m starting to feel like an idiot. Plus I don’t really feel the need to get into all the cock and vagina dentata talk that’s going to come with watching this film. Then again I do have some things to say about it, though; like the anti-colonial rape revenge logic–rape of anthropological exploration–to the way the genitalmonsters attack the arrogant white males in the film (with their exploration-as-domination/subjugation-including-sexual-subjugation attitudes; the way that one guy who gets attacked first was calling that snake thing “hey baby” and placatingly cooing that “she” was so pretty, the way you catcall a woman; by the way, I remembered the artist I was talking about at the end of that recent post on love and sex and racism in Berlin, it wasn’t Carolee Schneemann who took pictures of men who catcalled her, but Laurie Anderson) by literally feeding their phallocracy right back at them, choking them with it…

Okay, I started talking about it in spite of myself, ugh, what did Kafka write about Prometheus? “Everyone grew weary of the meaningless affair. The gods grew weary, the eagles grew weary, the wound closed wearily. There remained the inexplicable mass of rock. The legend tried to explain the inexplicable. As it came out of a substratum of truth it had in turn to end in the inexplicable.”

*

Back to looking at the O2 arena in Berlin. The multinational corporate spaceship it is, the universe it is (O2 World), the stage of evolution it represents: from one totalitarian state to another, commodification of every aspect of social existence, transition complete. The wall having been opened up, now opens up on this immense temple to capitalist spectacle. Advertisements play on a screen high in the sky. In the sky, in the air, in der himmel über Berlin, after Wim Wenders. Only instead of the angels who gaze upon us, we have Madonna and Lady Gaga to look up to (2:06). Before, the terrible angels loved us enough to reject their own immortality, to question and then repudiate the hierarchy that had produced them and that their existence continued producing. They came down so we could live together, love together, die together. Be in the world together. Then, they (we) believed in solidarity. But in this new World, the terrible angels don’t ever come down. They want us to keep looking up. Force us to keep looking up.

*

A coda for Prometheus. In my world, this would have played over the credits:

YOU CAN’T HIDE FROM THE TRUTH / BECAUSE THE TRUTH IS ALL THERE IS

*

Edited to add: egregious oversight on my part, the best soundtrack for a potential slave android insurrection with anti-colonial, racialized, gendered, queered, overtones is obviously Janelle Monáe:

PLASTIC SWEAT, METAL SKIN

METALLIC TEARS, MANNEQUIN

CAREFREE, NIGHT CLUB

CLOSET DRUNK, BATHTUB

WHITE HOUSE, JIM CROW

DIRTY LIES, MY REGARDS

I’M AN ALIEN FROM OUTERSPACE

I’M A CYBERGIRL WITHOUT A FACE A HEART OR A MIND

(A PRODUCT OF THE MAN, I’M A PRODUCT OF THE MAN)

SEE SEE SEE SEE

I’M A SLAVE GIRL WITHOUT A RACE (WITHOUT A RACE)

*

Edited to add (June 25, 2012): found via wretchedoftheearth and iwakeupblack, from Reagan Charles Cook:

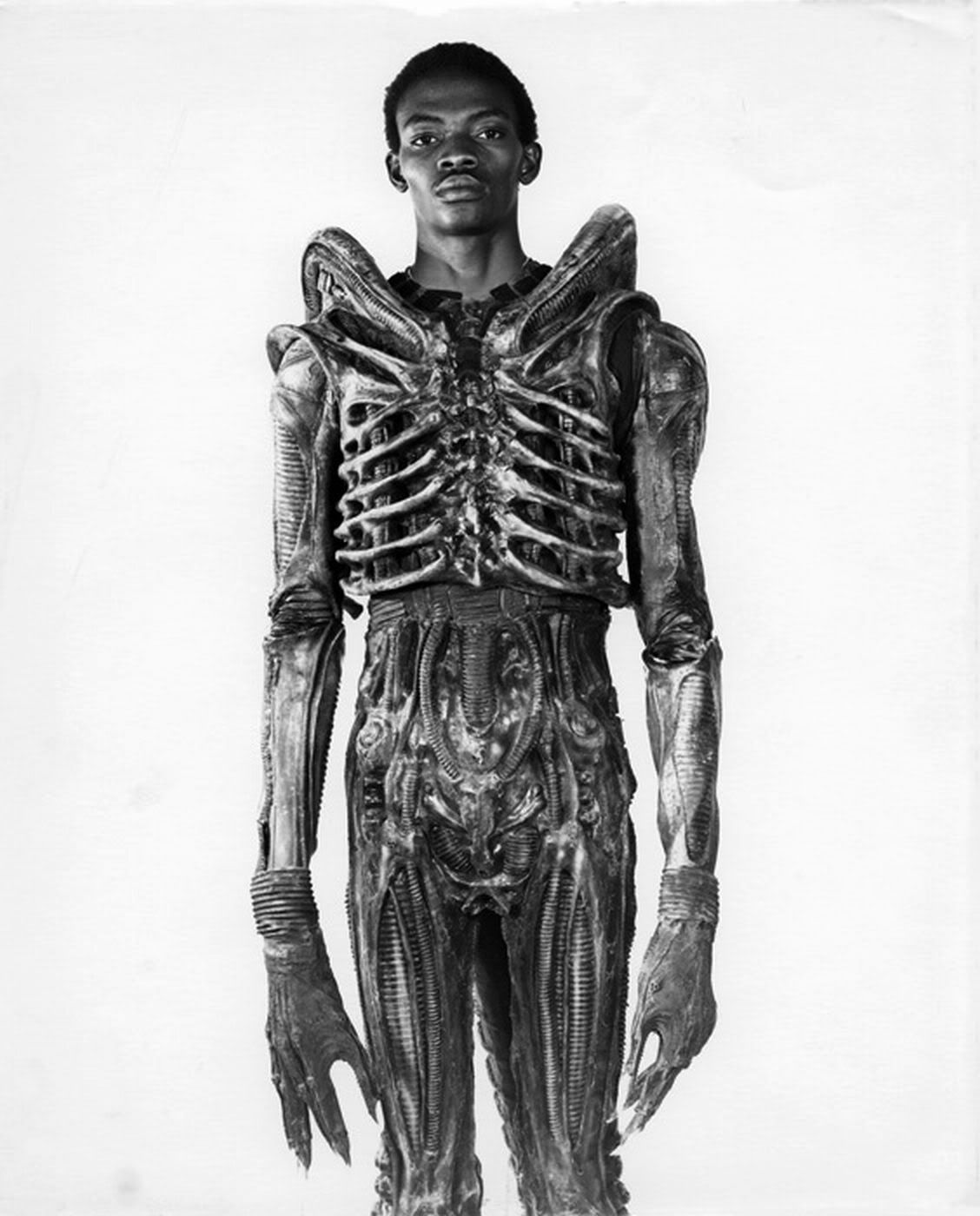

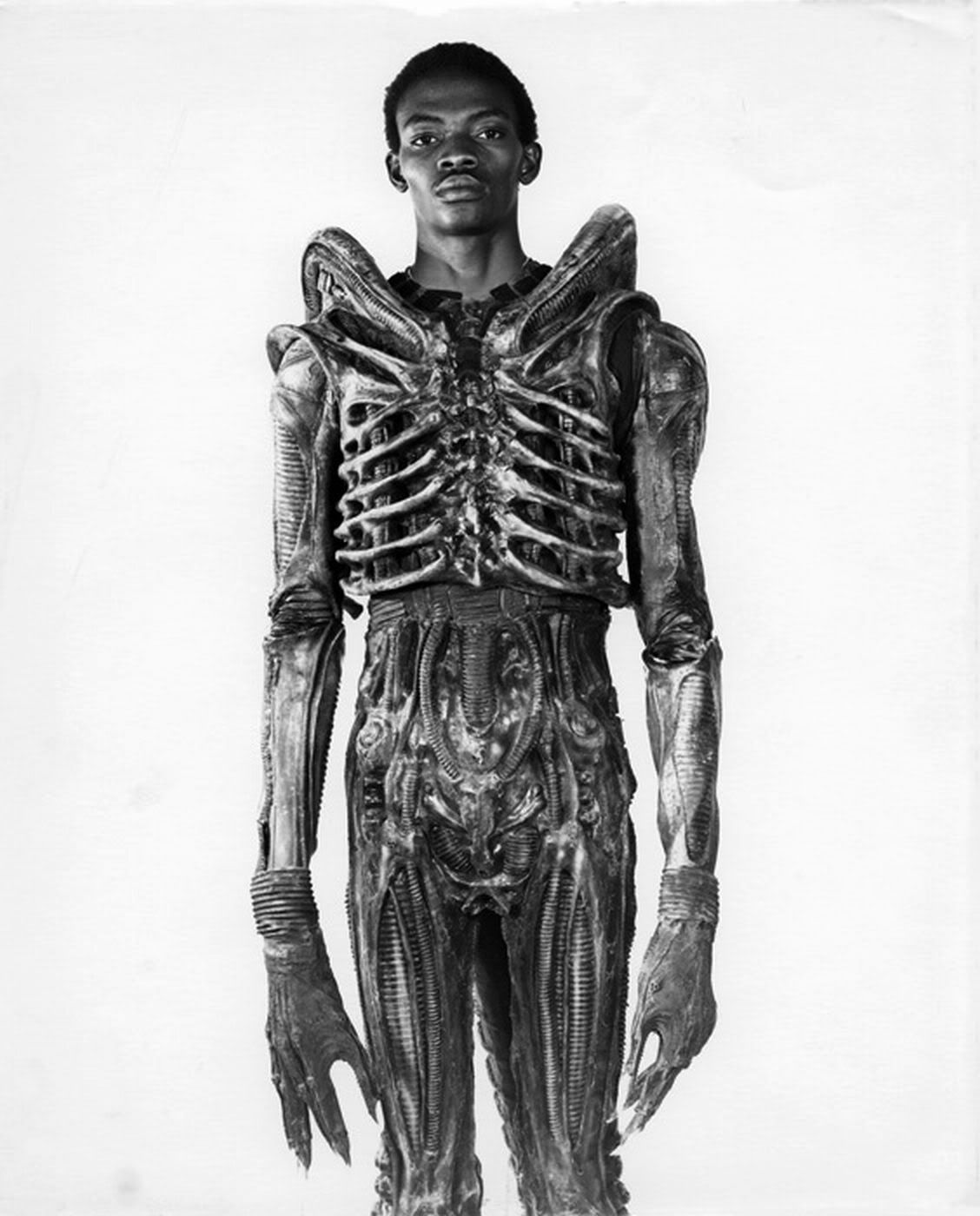

It never occurred to me to browse through the credits of Ridley Scott’s 1979 film Alien, to find out who was underneath the monstrous black mask.

The man was Bolanji Badejo, a 7ft tall Nigerian design student picked up from a bar in West London to fill the title role. He worked on the film for 4 months. Spending every day wrapped in a suffocating custom fitted rubber suit, working to exude a presence of pure evil.

Despite his incredible contribution to the film’s success Badejo never received any publicity for his involvement. Ultimately, it would be his only film role.

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: abortion, alien, androids, berlin, Bolanji Badejo, charlize theron, colonialism, david8, Deleuze, der himmel über berlin, elizabeth shaw, eric g. wilson, Guattari, handsome boy modeling school, idris elba, imperialism, janek, janelle monáe, jasbir puar, Kafka, Lawrence of Arabia, meredith vickers, Michael Fassbender, nomadology, noomi rapace, peter o'toole, prince faisal, Prometheus, Ridley Scott, war machine, weyland, weyland enterprises, wim wenders, wings of desire